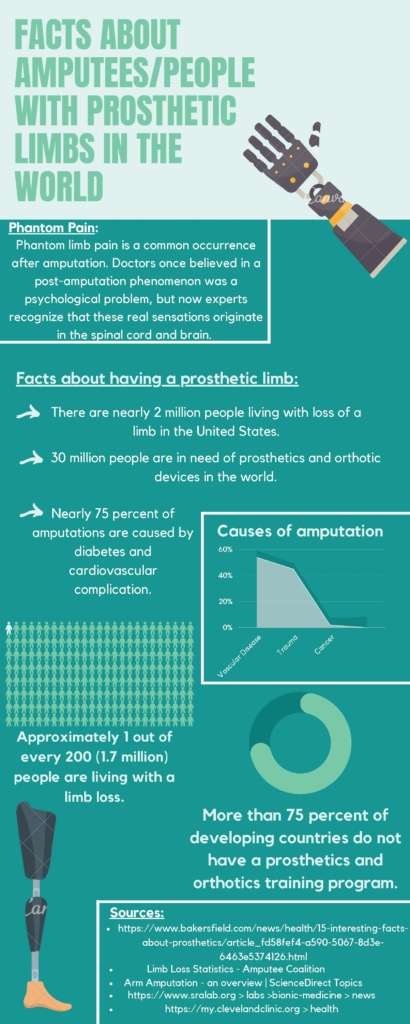

Losing a limb: “There is a purpose behind all things”

Chris and his family on a hike.

November 11, 2022

Chris Smith remembers skating down the ice, throwing the perfect pass and scoring the game-winning goal.

Then it all took a drastic turn.

He, like athletes all over the world, competes in the sports he loves, just differently: with a prosthetic limb.

The 37-year-old lost his right leg at age 16. A few weeks before his sophomore year at Bingham High School in South Jordan, Utah. Smith was going street lugging with some friends when he attempted to put his feet down to decelerate. The board’s wheels hit an unknown object on the road and sent him spinning out of control.

When he got to the hospital, he found out he had multiple compound fractures, including his tibia, fibula and femur and two arterial bleeds. The doctors wanted to try to save his leg but gave him the option of amputation.

Doctors told him that if they saved his leg it would make it an inch shorter, leaving Smith with the hard decision of either having a shorter leg and a limp or having it amputated.

“At the time all I could think about was getting a prosthetic leg and playing hockey again,” Smith said.

His leg was amputated mid-shin in November 2001. By December, he was walking and by April he was ice skating again. During the summer, he was participating in ice hockey camps.

“I was never as good as I once was,” Smith said.

Before the accident, he loved hockey and played regularly. After the amputation, he was determined to start playing again. When he turned 18, he made the senior team for the USA Standing Ice Hockey.

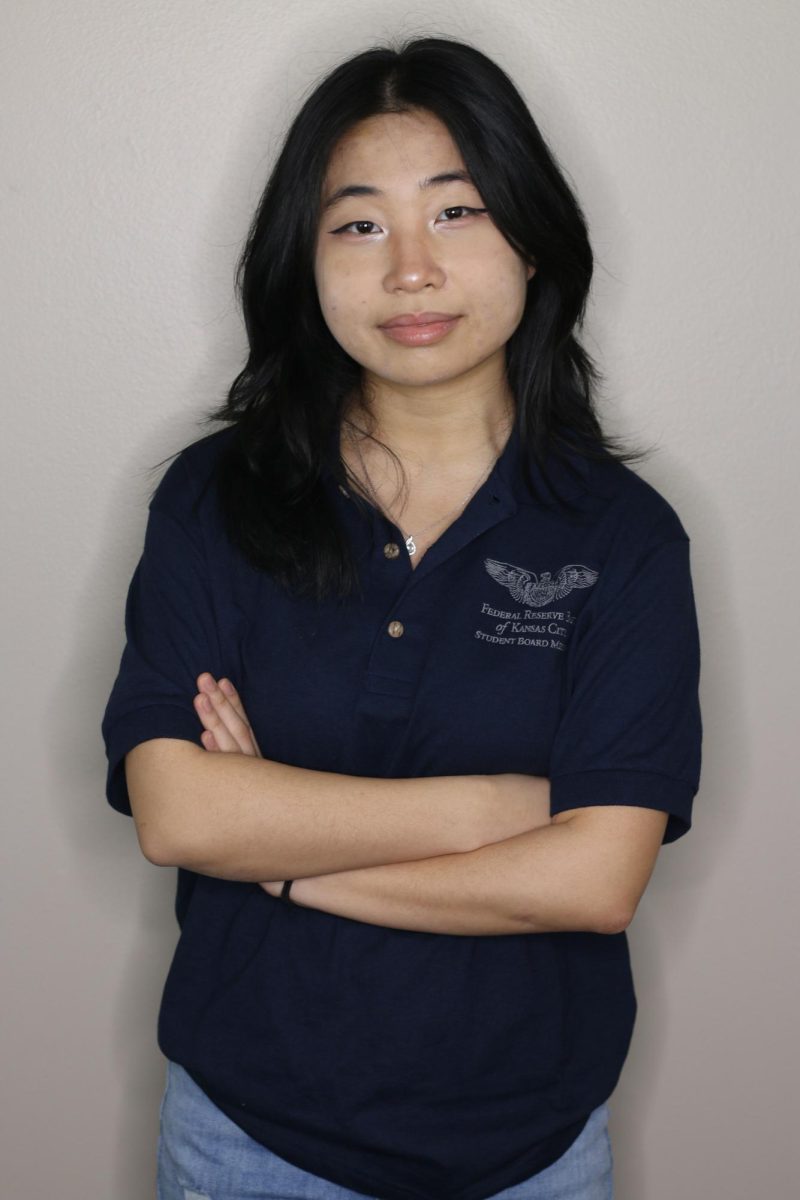

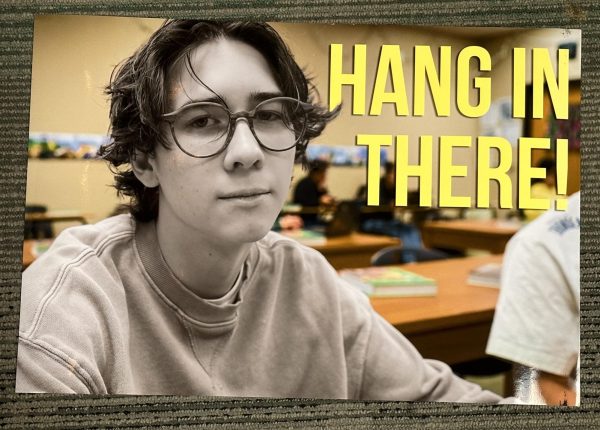

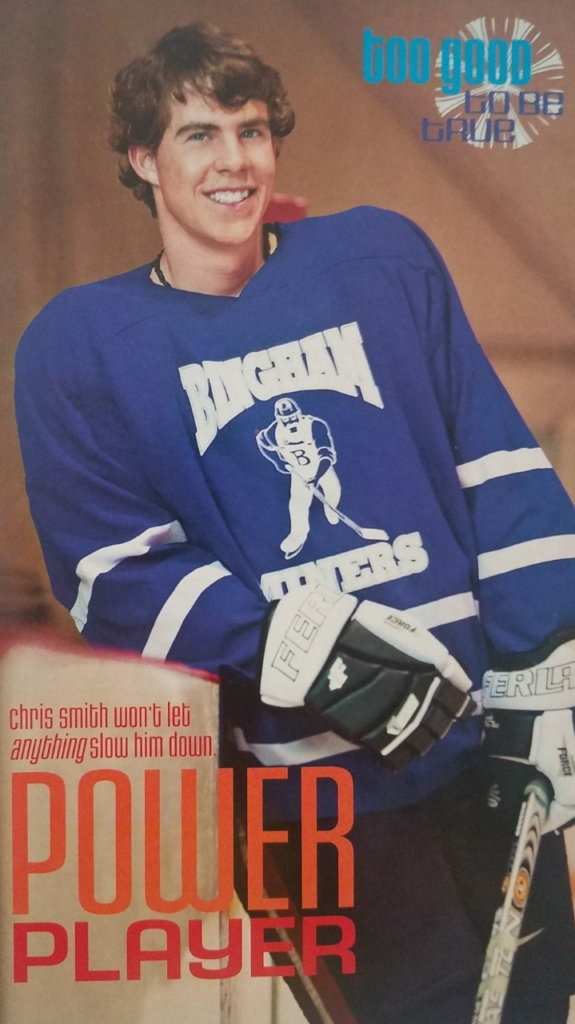

Chris Smith’s love of hockey preceded his injury. Years after losing a leg, he made the senior team for the USA Standing Ice Hockey. Courtesy of Chris Smith

“Playing hockey was my therapy emotionally and physically,” he said.

Smith said people often wonder when they see him if the prosthetic is an advantage or disadvantage.

According to Amputeestore.com, one small advantage to having a prosthetic leg is it typically weighs less than a biological leg.

Chris Smith’s love of hockey preceded his injury. Years after losing a leg, he made the senior team for the USA Standing Ice Hockey. Courtesy of Chris Smith

One disadvantage is excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis), which can affect how the prosthetic fits and can cause skin issues, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. Another is weakness in the residual limb, making it difficult to use the prosthetic for long periods. Wearing a prosthetic will also change the residual limb shape.

Mark Pitambersingh works for Hanger Clinic: Prosthetics and Orthotics in Norman, where he helps amputees adjust to first using prosthetics.

“It’s great working with the amputee athletes and watching them succeed and pushing themselves harder,” he said.

Smith and Pitambersingh said the rehabilitation process is definitely a struggle because amputees have to learn how to walk, write and stand all over again depending on which body part was amputated.

“It was the worst pain I’ve ever been in,” Smith said. “First week home I was thin and weak, but it came back quick.”

According to Main Line Health, amputees have to go through two rounds of rehabilitation. The first is immediately after amputation and the second is when they’re ready for prosthetic training. The patient has to stay at the hospital for seven to 14 days, with 76 percent of patients returning home upon discharge.

The process of getting a limb amputated and then going through rehabilitation is a struggle all amputees have taken on, Smith said.

“There is a purpose behind all things,” he said.